I haven't had an opportunity to take a class on making quills. So before trying it myself, I scoured the web in search of instructions. Most of what I found seems to agree on the basic steps, but the specifics vary.

- Prepare the feather — Cut off the tip, clean the membrane from the surface and inside of the barrel, trim it to length, and trim off the barbs to make holding it more comfortable.

- Cure the barrel of the feather (also referred to as tempering or dutching) — Fresh feathers are too soft and flexible to be cut and used as a pen. The barrel is hardened through aging or heat treating so it can hold its shape and last longer. The methods for this process vary quite a bit: from baking the feathers in an oven, immersing them in hot sand or boiling water, to rolling them against a heated metal surface.

- Cut the quill — The cutting of the writing tip. The steps vary in order, but the shape of the end result is the same.

Online Sources

I searched the web far and wide, and found useful information at the following sites:

- Dr. Dianne Tillotson's Medieval Writing page on The Quill Pen.

- No specifics on the amount of heat to cure the feather with.

- Excellent drawings of the cutting process.

- Regia Anglorum's background on quills and tutorial on cutting quills.

- Suggests a unique method of curing by immersing the feather into boiling water.

- Excellent line-drawn pictures of the cutting process.

- Lady Sunneva de Cleia's class handout on quill making.

- Great information on the curing process, relatively little on the nib cutting.

- Recommends soaking the barrels before tempering.

- Suggests that the sand be no more than 220°.

- Recommends 5 minutes immersed in the sand.

- Isaac Bane's A&S documentation on the preparation of quills, with lots of period references.

- Shows a tray of sand and indicates it sits in a 350° oven for 20 minutes.

- Feathers are immersed for "a few seconds".

- Liralen Li's page on quills.

- Great information on the cutting of the nib.

- Talks about the difference between curing after soaking in water and dry curing.

- Recommends making the ink slit by bending, not cutting.

- Another reference for heating the sand 15-20 minutes in a 350° oven.

- Leaves the feathers in the hot sand until it has cooled.

- Benyomen has a blog called Melechet Shamayim. He has three posts on the making of quills: feather selection, trimming the plume and curing it, and cutting the writing tip.

- Advocates for a long soaking period before curing.

- Recommends a direct heat curing method of placing the previously soaked feathers in a 200 degree oven for 15-30 minutes.

- Great pictures, drawings & discussion of the nib cutting process.

My first attempts

Trimming & cleaning — I cut the feathers to an overall length of the span of my pinky finger to thumb, stretched out. I stripped off most of the barbs. I scraped away the outer membrane and pulled out the inner membrane.

Curing — I decided to try soaking the barrels in water for 12+ hours first before curing them. A few of the sources I read recommend this to prevent the cured feather from becoming too brittle.

I filled a 28 ounce can with some fine white decorative sand from the craft store. After heating it for 20 minutes in a 350° oven, the center of the sand was 120° and the edges 150°. I decided to heat the sand longer before trying to cure with it. After about 10 more minutes, the middle of the container was about 160°, and the outer edges were 190°. Given one reference to "under 220°" and another for a 200° oven, this seemed to be a safe temperature to start with.

I plunged 3 feathers in the middle of the sand and 3 feathers near the edge. I removed one from each area after 5 minutes and 30 minutes. I left the remaining feathers to sit in the sand almost 90 minutes until it had cooled to 80°.

Regardless of where they were in the sand (center or edge), the 30 and 90 minute barrels were quite stiff, the 5 minute barrels still had a bit of flex to them.

Cutting — I opted to follow the directions from Regia Anglorum and Medieval Writing on how to cut the nib. It took a surprising amount of effort to cut through the cured feathers. I ended up have to whittle away at the cuts, taking small slivers of material off each time.

The feathers that were removed after only 5 minutes in the sand were definitely too soft. The barrels were easy to distort and the tines of the nib didn't want to stay together well.

The feathers that cured for 30 minutes cut well. Here are a couple images of one of the cut quills.

One of the 90 minute cured quills splintered when I attempted to cut it, I don't know if it was damaged before the curing process, or if it became brittle from being over-cured. The other cut just fine.

Writing — I think I could grow to like using a quill. When cured and cut well, they glide more smoothly over the paper than any metal nib I've used.

|

| One of the 5 minute cured goose feathers. Tines were too soft and wouldn't stay together, ink was difficult to get started. Note the split in the bottom of the 'c' in 'quick'. |

|

| One of the 30 minute cured goose feathers, the inside of the barrel of this feather has some fibers stuck to it. |

|

| A 30 minute cured turkey feather. Very stiff, seems to have thicker walls than the goose feathers which may have helped. |

|

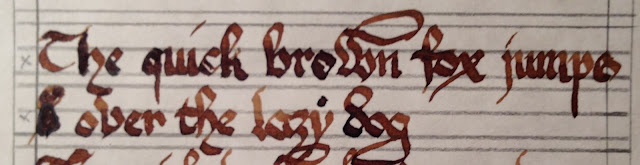

| The same 30 minute turkey feather testing different script. |

I noted a few key differences as compared to the metal dip nibs I'm used to:

- Because of the lack of reservoir, I had to angle my writing surface further away from me to about 45°, as well as keeping the tip of the quill a little lower than the body. Otherwise the ink would flow away from the tip and my lines would become faint.

- They hold more ink than I was expecting, but not as much as my favorite metal nibs with reservoirs.

- Because the tines are shorter and stubbier than metal nibs, it's a bit harder to see where the tip is and place it accurately on the page.

Final Thoughts

I'm very happy with my first attempts at making my own quills for calligraphy. I definitely need to experiment more with curing and cutting, as well as practice my calligraphy with them. There's a good chance my next scroll assignment will be written with a feather quill instead of a metal dip nib.

No comments:

Post a Comment